Why Does My Iliotibial-Band (ITB) Hurt When I Run? Considerations for Managing the ITB as a Runner5/30/2024

Sean RimmerRunning Specialist, Physical Therapist at Run Potential Rehab & Performance in Colorado Springs, CO.

Structure and Function of the ITB: The ITB consists of a thick fibrous connective tissue with upper attachments at the outer pelvis, glute max muscle, and tensor fascia lata (TFL) muscle near the pelvis; and the ITB spans the outer thigh to insert at the outer femur (thigh bone) and tibia (shin bone) near the knee joint. In the image below, you can get an idea of the ITB anatomy and that it further crosses 2-joints both at the hip and knee. The ITB has been proposed to function as a lateral stabilizer to both the hip and knee during the stance phase of running, while also aiding in energy storage and release. An example of the ITB’s function is during the initial contact through loading response phase of our running gait. When our foot first touches the ground, we tend to land slightly on the outside of our foot. Due to this contact, there’s a normal strain to the outer part of the leg. Our ITB functions to reduce excess lateral strain at the knee and hip. Secondarily, this allows the ITB to store some mechanical energy from the initial strain to provide some mechanical return after the loading response phase in our gait. Both of these functions are imperative to us as runners, for both stability and mechanical efficiency.  Cross Over Stride Cross Over Stride Why does ITBS occur? In the past, ITBS was thought to be friction related stress from the lower ITB “rubbing” the lower femur if the ITB was too taught. However, it is now theorized that ITBS is compression related. This compression is thought to occur when the knee is bent past 30 degrees and the ITB compresses against the outer femur at the knee. Though the ITB get’s the rap as the pain source, the pain site is thought to be the highly innervated fat pad between the ITB and femur. Now, if you’re reading this you’re probably thinking, well wouldn’t nearly every runner get ITBS if it occurs with only 30 degrees of knee flexion? Unfortunately, the answer is not straight forward, like with most running-related injuries. However, with coming across ITBS frequently, there are some common trends I tend to appreciate in individuals dealing with ITBS:

By no means is this an extensive list of causatory reasons to why ITBS comes on, nor is it guaranteed reasons for ITBS to come on. Rather these are patterns I tend to see on the movement and training side of running that have a potential to bring on ITBS. Training Error In previous articles I’ve written, training error tends to come up as a potential contributing factor for running-related injuries. Training error is multifactorial, but in simple terms, it’s excess stress with inadequate recovery. We need both stress and adequate recovery to have a higher potential to remain healthy as runners. With that said, our tissues have capacities before they either fail (major tissue injury), or become sensitized (become irritated or painful). Without discussing altered mechanics or compensation (which I’ll discuss below), if we don’t allow recovery within our training, there’s a higher risk for tissues that are stressed during running to become sensitized or injured. Without going too deep into training error, taking account of your total training load is important. Think of the total training load as the sum of our FDI principle: Frequency, Duration, and Intensity of training, and I would also include terrain, as varying technicality, steepness, and trail surface can have an affect on training load. Terrain Factors For the purpose of this article, I want to highlight terrain as an area of training error. There are two terrain factors that can place a higher level of strain to the ITB and they include downhill running and running on narrow trails. The downhill in general increases the overall load on the musculoskeletal system, where there’s often slight to significant over-striding. If the body isn’t conditioned for this, and or we increase our downhill running rapidly, there’s a potential ITBS could result. On the other hand, a narrow trail tends to narrow our step width as runners, and this can lead to an increase in lateral strain to the leg. As I previously mentioned, the ITB acts as a lateral stabilizer to the leg during the stance phase of running, and with the ITB being on the lateral portion of the leg, it tends to take on more strain as our step width narrows. Again, this situation can become a problem if our tissue isn’t ready to handle the load of the terrain specifically. Long Ground Contact Time/Over-Striding Another pattern I’ll often visualize when assessing someone with ITBS, is a longer ground contact time (GCT) and/or over-striding. To define these two terms: GCT is the amount of time our foot is on the ground from initial contact through the push off phase of running, and over-striding is when the shin angle increases past perpendicular; or a better example to conceptualize this would be when the foot lands in front of the knee at initial contact. There’s no clear evidence or patterns I’ve appreciated that speak to the degree of over-striding or GCT as a cause of ITBS, but often intervening to improve on either or both areas can be helpful in reducing symptoms in the long-term for ITBS. Narrow Step Width/Cross-Over Stride Both a narrow step width and a cross-over stride have the potential to lead to ITBS. This is due to an increase in ITB strain as the foot moves closer to midline during the stance phase of running. A cross-over stride is when the foot lands past the center point of the pelvis in the horizontal plane (past midline). We’ll discuss some simple, yet effective intervention strategies for step width in the management section.  Increased Step Width Increased Step Width Reduced Pronatory Mobility/Control at the Rear-Foot The mobility and control in the foot and ankle are imperative during the stance phase of running. The motion in these joints dictate what may occur up the kinetic chain, whether it’s complimentary or compensatory movement. Pronation is when the foot and ankle are in a state of storing energy and/or absorbing load. The motions that occur within pronation are ankle dorsiflexion, rear-foot eversion, and abduction of the foot. If our foot and ankle can’t manage loading optimally, compensatory motion can occur both locally or up the kinetic chain. One of the compensations I’ll often see is someone narrowing their step width to increase the relative pronation at the foot and ankle. When the step width becomes increasingly narrow, the body has a higher leverage to increase rear-foot eversion torque which aids in pronation. Though this correction aids in one issue, it can potentially lead to another problem, that of ITBS. Management Strategies for ITBS: Early Phase In the early stage of managing ITBS, it’s important to encourage movement as tolerated, to address the underlying training error or potential biomechanical compensation, and early loading to the ITB specifically. We want to treat ITBS like a tendinopathy (pain within a tendon), as the ITB responds to treatment in a similar fashion. What this often means, is that we can have some minor discomfort with movement, while we’re improving the tissue loading capacity and tolerance to the activity, ie. running. Here are a few examples of what a treatment could look like for someone dealing with ITBS in the early stage or when the ITB is irritable: Activity/Running Progression Uphill treadmill walking → Progressing to uphill treadmill run/walk Running Biomechanical Changes Cues to “widen” the step width (this can be practiced by jogging on a track while straddling the line and not stepping on the line). Or increasing step rate (cadence) as this tends to shorten our stride length and potentially reduce over-striding/cross-over step.  Loading the ITB in Non-Weight Bearing (R Leg) Loading the ITB in Non-Weight Bearing (R Leg) Loading the ITB Initially, this can be done in non-weight bearing if the ITB is highly irritable, but should ultimately be progressed to weight bearing. I like to use a lunge or split squat pattern as a movement to load the ITB as it lengthens the tissue at the hip and the knee when the knee is bent and hip is in extension. A progression could start with someone lying on their back on a PT table or bed with their ITBS leg hanging off the side of the table. If they then slowly work the bending portion of the knee, this can slowly begin to load the ITB in a lengthened state. If this is tolerable, and non-symptomatic, someone may be able to tolerate a lunge isometric (hold) at bodyweight, the depth can be modified based on symptoms. The leg that is back is the leg we are focusing on loading for the ITB.  Rear-Foot Elevated Split Squat Rear-Foot Elevated Split Squat Management Strategies for ITBS: Late Phase In the late stages of managing ITBS we want to progress tissue loading in weightbearing with the addition of external load, add plyometrics with a lateral component to increase loading demand to the ITB, and progress run training via FDI principle and gradual exposure to the terrain that may have contributed to the ITBS. Activity/Running Progression (Terrain) Uphill running→ Flat running → Gradual downhill →Steep downhill → More technical steep downhill & single-track trail (narrow) Loading the ITB Lunge in place —> Rear-foot elevated split squat → Adding external load through a larger range of motion  Skater Hops Skater Hops Plyometrics Hopping with both feet side to side → Skater hops side to side → Lateral single leg hops at a higher amplitude Again, it’s important to state that by no means is this a “cookie cutter” approach to managing ITBS as everyone’s situation is unique to them. The intent of this article was to educate on the anatomy and function of the ITB, considerations for why ITBS can come on in runners, and some management options and progressions if dealing with ITBS. Article provided by SheelsScheels is a Pikes Peak Marathon partner, original post 9/1/2023  Training in extreme weather can be a challenge—running in mid-summer heat can be just as difficult as those sub-freezing runs. No matter the temperature, the right running clothing can make all the difference. Although hot and humid weather requires different layers than a snowy, windy run, there are specific features to look for when it comes to running clothing. Whether you’re needing running clothing for summer or winter, our Running Experts share exactly what to look for so you get the most out of your run. Pay Attention to Fabric Content No matter the temperature, look for clothing made of a blend of polyester, spandex, or nylon. These materials are best for running because they are engineered to be lightweight and breathable as well as wick away moisture to keep you feeling comfortable. Avoid reaching for that cotton shirt or pair of socks—it’ll leave you cold, damp, and distracted throughout your run. Learn more about why running-specific socks are important, straight from our Footwear Experts: Do Running Socks Make a Difference? Running Clothing Features Today, clothing is loaded with technologies and features to help you perform your best—and running-specific clothing is no different. When looking for new running clothes, consider these features and technologies:

What to Wear Running Throughout Seasons If you live in a climate that has all four seasons, your running wardrobe will include a whole range of different layers to accommodate the variety of temperatures. Our Running Experts highlight some basic layering options, but it’s important to remember that everyone’s preferences are different so find what works best for you. Expert Tip: Dress in layers that you can easily take off and tie around your waist.

No matter the weather and temperature, proper running clothing is key for a comfortable and successful run, so pay attention to the fabric content, features, and technologies available in running clothes. If you have additional questions about running gear, stop into your local SCHEELS to speak with an Expert. CINDY KUZMAPublished September 7, 2021 for Outside: Women's Running  Photo Credit - Skip Williams Photo Credit - Skip Williams Female bodies just might be built for the challenge of greater distance—as are our minds and hearts. Here, we dig into the science of endurance. Ellie Pell blazed across the finish line of the 2019 Green Lakes Endurance Run—a 50K trail race—in 3:58:37, nearly eight minutes ahead of second-place finisher Richard Ellsworth. Race organizers were so surprised a woman bested the 90-athlete field they didn’t even have a trophy for the top male runner. Pell, then 27, carried home two wooden plaques bedecked with greenery, one for the overall winner and one for first-place female, while Ellsworth’s was custom-made and shipped to him later. In some ways, you can’t blame the race directors. At nearly every distance from the 100 meters on up, the fastest women tend to finish behind the fastest men. And though records of women swiftly covering significant ground appear in history—in 1,000 A.D., for instance, a Scottish slave named Hekja would reportedly run for days on end on missions from her master—modern times haven’t always offered them the opportunity to try. As recently as 1968, women were barred from running more than 800 meters in the Olympics, lest their reproductive organs tumble out or their frail bodies fall apart. But from another perspective, Pell’s victory shouldn’t have come as a shock. Joan Benoit Samuelson claimed victory in the first Olympic Marathon in 1984, and women haven’t stopped pushing their limits since, including in distances that far exceed 26.2 miles. As the sport of ultrarunning increases in popularity—according to a large study earlier this year by RunRepeat and the International Association of Ultrarunners, participation has exploded by a factor of more than 16 since 1996—more women than ever are claiming spots at the starting lines. Female athletes now make up 23 percent of the more than 600,000 ultrarunners annually, up from 14 percent in 1996. And increasingly, women are finding themselves first to the finish. Ann Trason may be the pioneer of the trend: Back in 1989, she claimed the 24-Hour National Championship outright by logging 143 miles, about three and a half more than second-place finisher Scott Demaree. She twice finished second overall, beating all the men but one, in the 100-mile Western States Endurance Run, a prestigious event often called the Super Bowl of ultrarunning. "The mentality is so different now, and it gives room for women to push themselves harder, reach their full potential." Then came Pam Reed, who in 2002 and 2003 crossed the line first at the Badwater 135, an arduous journey through Death Valley, California, in which temperatures often reach above 120 degrees Fahrenheit. Reed, now approaching her 60s, is still racing—against a new crop of runners eager to carry her torch forward. Courtney Dauwalter has notched outright victories in everything from 24-hour races to 50-milers to the 2017 Moab 240 Endurance Run, where she beat the first man by 10 hours. Camille Herron has claimed the top overall spot in 24-hour and 100-mile events. And last October, Maggie Guterl became the first woman to be the last person standing in Big’s Backyard Ultra, a unique competition that involves completing the most laps possible of an approximately 4-mile loop. She endured for 60 hours and 250 miles. It’s a transformation that has occurred largely in a single lifetime. When sport psychologist Joan Steidinger, Ph.D., was in high school in the 1970s, her parents wouldn’t allow her to run cross country because it was “unladylike.” But she picked up running later on, ran her first ultra—the 28.4-mile Quad Dipsea—in 1991, and then kept going, eventually finishing races like Western States. “The mentality is so different now, and it gives room for women to push themselves harder, reach their full potential,” says Steidinger, the author of two books, Sisterhood in Sports: How Female Athletes Collaborate and Compete and Stand Up and Shout Out: Women’s Fight for Equal Pay, Equal Rights, and Equal Opportunities in Sports. “They’re winning races, and by hours and hours. It’s remarkable, and I think women’s potential is just beginning to be tapped.” Bodies Built for Distance World records at every distance from 100 meters to 100 miles belong to men by a margin of around 10 to 12 percent, and for largely biological reasons. For one, women have less muscle mass. Pump for pump, women’s smaller hearts shuttle less blood through their bodies. And with lower levels of the protein hemoglobin, each drop of that blood contains less oxygen, which working muscles require to produce energy. Of course, world records match the best against the best. “You’d assume that there’s an equal number of people who have gone for it,” says Megan Roche, M.D., who studies athletes’ genetics and health—and is also a five-time national ultrarunning champion. “But at longer distance races, it’s so dependent on who shows up.” And as more women take their place in the field, there’s added evidence that the longer the runway, the more ground they make up. At distances beyond 195 miles, women on the whole are .6 percent faster than men, the RunRepeat/IAU study found. As the miles pile on, the differences that hold women back in shorter events become less crucial. No one’s sprinting through 100 miles in the mountains, making cardiac output less crucial. In fact, there are some unique characteristics of female physiology that lend themselves to success at superlong efforts. “In some ways, we were made to go longer distances,” Guterl says. Women, on the whole, tend to have more body fat than men, and higher levels of the hormone estrogen enable female bodies to turn that adipose tissue into energy, Roche says. In the later miles of a very long race, fat may be just about the only fuel left: The stores of energy called glycogen in muscles last only about 75 to 90 minutes, and while ultrarunners are notorious for eating everything from gels to soup to flat Coke and tacos to supply more glycogen, it’s impossible to replace every calorie. Another advantage may lie buried in muscle fibers. Women’s muscles appear to contract less forcefully than men’s, which is another reason for their slower top speed. But research suggests that women’s muscles also possess greater ability to fire over and over with less fatigue. In one study done of men and women before and after the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc in France, men showed more signs of burnout in their quads and calves at the end of the 110K distance. Many have theorized that thanks to childbirth, women feel less pain—or at least, have the capacity to endure more of it. While science hasn’t yet settled this—one large research review suggested women actually feel pain more intensely—there’s no doubt many top female ultrarunners can withstand extreme duress. “Anecdotally, I have worked with some women who had a massive pain tolerance, and it’s pretty cool to see that play out over the longer distances,” Roche says. “It’s like, OK, I’ve been projectile vomiting for the last 13 hours, but I’m going to keep putting one foot in front of the other.” Tougher terrain and unique race formats, such as Big’s Backyard, further level the playing field. Race director Lazarus Lake invites runners to his property in Bell Buckle, Tennessee. Each hour, they must complete a 4.16667-mile loop; hurt or exhausted runners drop one by one until only the winner remains. “I don’t think anyone really doubted a woman could win,” Guterl says. Dauwalter came close, in 2018, losing to Johan Steene only after both had run 33 miles beyond the point any previous years’ competitors had reached. The next year, knowing that people—including Lake—were rooting for her as the first woman definitely gave Guterl an extra boost. “You have to be internally motivated,” she says. “But you definitely feel like you can’t let people down.”  Pikes Peak Ascent - Photo Credit - Jack Hulett Pikes Peak Ascent - Photo Credit - Jack Hulett "Standing at the start line, I’ve always prepared as best as possible for everything I can predict will maybe happen, but then I’m acknowledging that there’s going to be some wrenches thrown in the day that I just couldn’t predict." Now that women have more opportunities than ever to show what they’re made of, these fast foremothers are likely to pass endurance-enhancing traits down to their offspring. “Our cells make changes every time they turn over—it’s called epigenetics,” says Rhonna Krouse, MS, an associate professor of exercise science at the College of Western Idaho who’s run ultras herself and also studied other athletes. Through training adaptations, nutrition, and the environment in general, our very DNA is altered. “We’ve only been evolving as athletes for such a short period of time. It makes you think: Where can we go?” The Endurance Mindset Of course, as Guterl alludes, there’s another crucial element in ultrarunning: psychology. Though it’s less easily defined in studies and statistics, women at the top of the sport cite it as an indisputable advantage. “The longer you go, it breaks you down so much physically. The things that normally differentiate a man from a woman—more blood volume, more muscle mass, higher VO2 max—all those things don’t really matter as much,” Herron says. “Then it just becomes your mind trying to will your body through fatigue. I think there’s less of a differentiation between men and women mentally.” Many of the psychological characteristics essential to superendurance align with typical female athlete traits, Roche says. That includes the focus, concentration, and discipline to toil daily in training and over long hours on the course, and the resilience to simply not quit when pain sets in—or when you’re struggling to stay awake, or hallucinating, says Dauwalter, who’s “seen” everything from pterodactyls to puppets playing on a swing set to a woman churning butter while racing. Staying calm and problem-solving when an injury strikes or you go a few miles off-course also plays a key role. The top female ultrarunners see those occurrences not as obstacles, but opportunities to apply lessons from the past—or learn new ones. (This—in addition to the fact that trail surfaces have less injury-inducing impact—is one reason women can also appreciate and excel in ultrarunning as they age, Roche says; the more experiences you’ve had, the more resources you can draw on.) “That’s part of the fun of these races and part of the puzzle,” Dauwalter says. “Standing at the start line, I’ve always prepared as best as possible for everything I can predict will maybe happen, but then I’m acknowledging that there’s going to be some wrenches thrown in the day that I just couldn’t predict. The make or break of just how successful the race goes is how you handle those wrenches that get thrown in and how you can keep your cool through fixing them.” Approaching an event this way requires a healthy dose of humility, an ability to admit your mistakes and learn from them, Guterl points out—another common, if not uniquely, female trait. One way this may manifest is in pacing. Studies suggest women are better able to check their egos and start a race at a reasonable effort, which enables them to pick things up later in the race. As Guterl puts it, “you see a lot of dudes go out super-fast, but you pass most of them later.” But there’s a role for confidence too, which top female athletes undoubtedly possess. Most grew up without seeing themselves as limited or inferior. Dauwalter has two brothers, and says her parents didn’t place her in a separate category or suggest she couldn’t do certain activities because she was the only girl. Herron always played basketball with neighborhood boys, and never thought of them as being better or stronger. When she started running ultras, she noticed men surged forward while women held back; she naturally took her spot near the front and never let herself fade. Curiosity, too, is what often leads women into the sport of ultrarunning in the first place, and it keeps them striving. After a few years of road marathons, Guterl became intrigued by an ultra in July in her then-hometown of Philadelphia. “I thought, ‘What’s it like to go this far? Can I do it?’” she says. And once she succeeded, she had new questions: “Can I do it better, or see how it is to go farther? I don’t really think I’m that fast, so the distance is where I think I excel.” That hints at another key trait of successful ultrarunners: an ability to accept and embrace different types of goals. Often, the top aim in a grueling ultrarace isn’t to nab a specific place or time, but merely to finish, something Krouse had known from her own experiences as an athlete. And when she surveyed nearly 350 female ultrarunners for a study published in the Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, she discovered she wasn’t alone. While road racers at distances like the 5K and marathon are often motivated by pace targets or body composition goals, especially weight loss, ultramarathoners expressed far different attitudes. “Their top motivation was actually this sense of being,” she says, something less tangible that they achieved by facing their biggest doubts and fears and overcoming them. It’s a shift on the normal balance between extrinsic motivation—for an outside reward, like recognition or a medal—and intrinsic motivation, a drive to participate in an activity for its own sake, and the personal rewards it provides. High-level athletes usually possess both, and in most sports in approximately equal amounts, Krouse says. But in female ultrarunners, the split seems to be somewhere around 75-25 in favor of individual transformation over external approval. Somewhat ironically, it seems, the ability to let go of the goal of dominating may actually power women to the tops of podiums, simply by focusing on one small step at a time and staying open to opportunity when it arises. “I never go to a race thinking I want to win,” Pell says, though she admits it’s fun when it happens. “Even if there were no races, I would still do workouts and run like I am now because I love the process. I love the journey.”  Pikes Peak Ascent Photo Credit - Jack Hulett Pikes Peak Ascent Photo Credit - Jack Hulett Stronger, Together Of course, some women are motivated by victory, especially in competitive races like Western States. In 2019, Dauwalter explicitly aimed not only to defend her title—she won in 2018 in 17 hours and 27 minutes, the second-fastest women’s time ever—but also to break the course record. But even when their competitive switch is flipped, women are adept at balancing aggressive tendencies with collaborative ones. “Women, if you get them at their best, go in a circle with each other—they really can respect their competitors,” Steidinger says. For Dauwalter, winning involves not an elbows-out battle against other racers, but a shared struggle to conquer the course; performing well elevates everyone. “Competing in a race with a ton of strong athletes helps you bring out your best. You can lift each other up by bringing the best version of yourself to a race, and then hopefully, it lifts the rest of the field up,” she says. “Everyone can see what their potential is, find their limit for how fast or how far they can go.” That philosophy fits naturally with the trail and ultrarunning communities, which athletes describe as open, welcoming, and “chill.” Men and women alike tend to be accepting, inclusive, and collaborative, making it easier for new athletes, including women, to enter the space. It also aligns with the type of mentorship many women naturally provide, Krouse says. Those with big goals in the sport usually don’t insulate or isolate in relentless pursuit of them. Instead, they dedicate themselves to helping each other achieve. For instance, Guterl is contemplating an attempt at an FKT—Fastest Known Time, a mark clocked on a given route that’s not an official race course—on Nolan’s 14, a run over 14 mountaintops in Colorado all above 14,000 feet. Meghan Hicks, the first female finisher, started a Facebook group for other women with the same idea in mind. There, they share tips on routes and techniques; Hicks was one of the first to congratulate Sarah Hansel when she claimed the FKT. “It’s just cool to see everyone encouraging everyone else to go for it, even if it’s your own record,” Guterl says. “They’re made to be broken, as they say.” The same spirit of collaboration often applies even mid-race, Krouse says: “You feel like you’re all allies out there on the course.” Dauwalter has literally been lifted out of a mud puddle mid-race. Then there’s what happened at last year’s Western States, when a hip injury struck Dauwalter at about mile 80. Pain shot down her leg and her pace slowed to a walk. Even as she felt her dream slipping away, she whooped, hollered, and doled out hugs when other women passed her, including eventual winner Clare Gallagher. And even though she wound up dropping out of the race, she wouldn’t have dreamed of being anywhere else but the finish line to watch Gallagher and others stream in, she says. The Next Frontier Scientists like Roche aren’t sure if women can ever completely outrun men at any distance. But Herron, for one, won’t let that stop her from trying. “The longer I go, the closer I come,” she says, noting that until Zach Bitter set a new men’s 100-mile record in August 2019, her 12 hours, 42 minutes, and 39 seconds was only 8 percent off the men’s mark. “I want to go 48 hours, six days, 1,000 miles. The question is, how far do I have to go that I could potentially maybe surpass the men’s world record?” At times, it feels like eclipsing men is what’s required to attract equal attention to female athletes, Guterl laments. Male FKTs, for instance, are more often covered in running media than women’s. That relative lack of visibility could be one obstacle to drawing even more women into the sport. So, too, could a fear of being on trails alone, event entry policies that favor men, and limited racial diversity—women of color, failing to see many others who look like them, might shy away. Grassroots groups like Trail Sisters and advocates like Mirna Valerio are trying their best to communicate that trail and ultrarunning really are for everybody—and raise the profiles of women in the sport for all to see. Races like Western States and the Hardrock 100, which have entry policies based on previous participation that skew male, could continue evaluating options to allow in more diverse fields, Guterl says. And as for the fear of being alone on a trail—more running groups may be the solution, though she points out that trails aren’t necessarily any more dangerous than city streets, and may even be safer. While the COVID-19 pandemic may have temporarily made ultraraces inaccessible to everyone—Western States, Hardrock, Badwater, and more were all canceled for 2020—the rise in virtual racing may actually draw more athletes into the sport. Lake called off his infamous 100-mile-ish Barkley Marathons in May and instead staged the The Great Virtual Race Across Tennessee 1,000K, in which more than 20,000 participants signed on to log 635 miles between May 1 and the end of August. “It’s inspiring for all of these people to come together to do this that wouldn’t have had access otherwise. Laz’s races are really hard to get into,” Roche says. “Innovative solutions are coming out of this, and it might transform running in the long term.” And in the end, that might give even more women the opportunity to themselves be transformed, following in the footsteps of the ultrarunners who came before them. Dauwalter is as humble and effacing as a record-holder and champion could be, but says she’s glad if her victories inspire others to strive. “I love hearing people’s stories and that they’re trying a new distance or going after something that sounded too hard or impossible initially,” she says. “In general, we always set the bar too low for ourselves. If people can start to see this thing they thought was their limit isn’t, and they can push past that—I think that’s pretty cool.” Injuries and Trail Running - Considerations for Management of Lateral Ankle Sprains In Trail Runners2/14/2024

Sean RimmerRunning Specialist Physical Therapist at Run Potential Rehab & Performance in Colorado Springs, CO As trail runners, it’s only a matter of time until a running-related injury (RRI) occurs as that’s the unfortunate reality of our sport. A RRI can occur due to a traumatic event or from repetitive/overuse microtrauma. One of the most common traumatic RRIs I see in trail runners is the lateral ankle sprain (LAS). In this article, I’ll highlight the mechanism of injury and tissues involved within a LAS, considerations for managing the recovery, and returning to running.  Lateral Ankle Sprain (LAS) There’s a high prevalence of LAS in trail runners due to the variable and often less predictable terrain. A LAS often occurs when the foot comes in contact with a rock, root, or unpredictable surface, and the body isn’t able to compensate in time to prevent the foot from rolling outward (excess supination). If the mechanism of “rolling the ankle” is stressful enough on the lateral ligaments between our outer shin bone (fibula) and rear-foot (talus and calcaneus) the ligament(s) is sprained. Ultimately, the ligament sprain occurs when the stress (force) exceeds the ligament’s capacity to prevent excess strain (deformation). The most common ligament that is sprained during a LAS is the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), and second is the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) (The ligaments are named from the bony attachments they share). Ligament sprains are graded based on the severity from grades ranging 1-3: A grade 1 sprain is when the tissue is elongated with micro-tears, a grade 2 sprain is when the tissue involves a partial tear to the ligament, and a grade 3 sprain involves a complete tear/rupture of the ligament. The higher the grade, the longer the recovery time and risk of chronicity. The healing-time frame for grade 1 LAS is typically 2-3 weeks, grade 2 is typically 4-6 weeks, and grade 3 is around 12+ weeks. When I say “healing time” that’s more of a definition of the ligament tissue itself healing, but what’s more important during the recovery process is restoring rear-foot/ankle range of motion (ROM), strength, coordination at the foot/ankle, and confidence to move/return to running. Unfortunately, if you’ve dealt with a LAS at least one time, the likelihood of you dealing with another, or multiple in the future, skyrockets. This is in part due to the ligament itself not being able to return to its previous physiological state of tension, but also if you haven’t restored the foot and ankle ROM, strength, and coordination; this leaves a fault in the movement quality at the foot/ankle which can increase the risk of chronic ankle instability (CAI). Foot & Ankle ROM Considerations In the early phases of a LAS, from days to the first 2 weeks, the primary focus is to reduce local swelling, restore weight-bearing function as tolerated, active ROM as tolerated, and to restore the ability to walk. Once swelling is down and walking is normalized, it's imperative to restore ankle dorsiflexion and rear-foot eversion in weight bearing. The pattern I often see in both acute LAS and in individuals with CAI is that the rear-foot is limited in eversion. When the foot and ankle are limited in dorsiflexion and eversion, this tends to leave your foot in a slightly supinated position (plantar flexed and inverted). This becomes problematic when your foot and ankle can’t properly load into the ground which increases the risk of recurrent LAS. There are a variety of exercises and mobilizations that can improve ankle dorsiflexion and rear-foot eversion, but here are my top 3 that I’ve found to be successful. 1. Active ankle inversion/eversion inverted “U” exercise: This exercise includes slow and controlled foot/ankle movement starting in some ankle dorsiflexion and inversion, moving up into ankle plantar flexion and inversion, then to ankle plantar flexion and eversion, and then ankle dorsiflexion and eversion. Then you reverse. The movement ends up looking like an inverted-U. This can be done with both feet or one, from the ground or on a slant-board, and with external loading all as progressions or regressions to meet the individual.

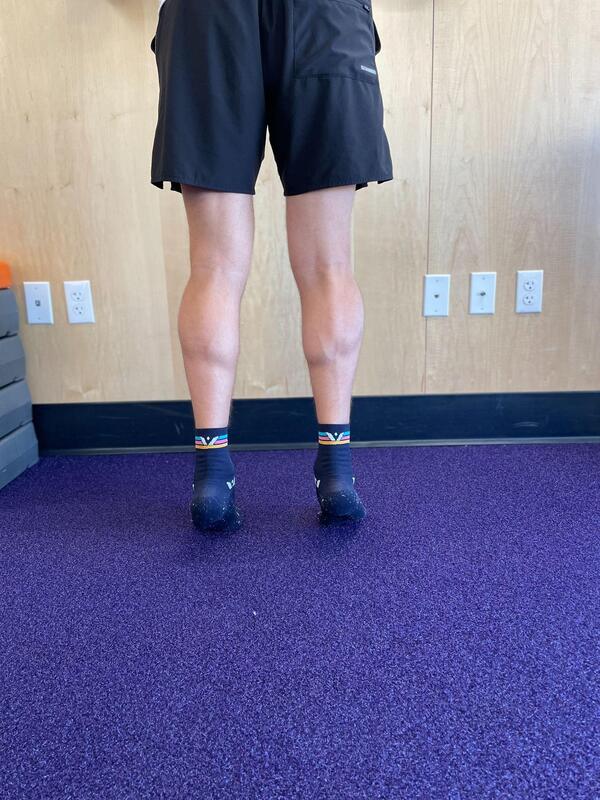

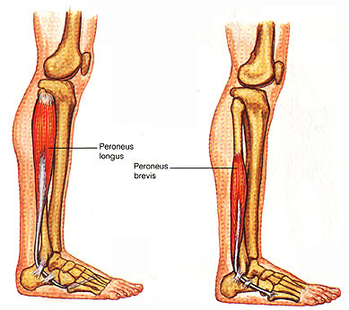

If all of these motions are restored and controlled under active load, we can then build specific strength and movement control to enhance recovery and reduce the risk of CAI. Foot and Ankle Strength Considerations Improving strength around the foot and ankle is also highly important to improve tissue resiliency; though a specific area to improve strength post LAS would be via the peroneal muscles. The peroneal muscles include the peroneus brevis and longus. Both muscles originate in the lateral lower leg and have long tendons that wrap behind our lateral malleoli attaching to our lateral midfoot (peroneus brevis) and the medial plantar surface of our foot (peroneus longus). These muscles help transition the foot from inversion to eversion after initial contact through loading response. The peroneal muscle-tendon units also act as an active “guard rail” to the lateral ankle/foot to control excessive supinatory motion. To improve the functional strength of this muscle group, we need to work the muscle group in plantar flexion and eversion as that’s it’s primary function. My favorite strengthening exercise variation is as follows:

Motor/Movement Control Motor control is dictated by both our past movement experiences and pain. Following a LAS, our motor control is impaired due to pain and the mechanical property changes in the region of the foot and ankle (due to the ligament strain or tear). This is our brain and body’s way of protecting us from not doing more than we can handle on our ankle. Initially, this is a good thing, but as we restore ROM and normalize our walking gait, our motor control at the foot and ankle should progress. Progress in motor control does not occur overnight, but rather gradually with a combination of movement practice/repetition (of how we desire to move) and with progressive movement challenge (ie. more dynamic or progressive load). Furthermore, our motor control progress is on a continuum, from the initial stages of returning to a normalized walking gait to eventually running fast on technical trails. Our body and brain need to take the “stepping stones” through movement practice and progressive challenge to have the movement confidence to progress through the motor control continuum. This means that the rehab process should reflect the progression of loading/challenge of movement to ultimately meet the demands of the end goal (ie. running technical trails). It’s important to note that confidence to move/run should also progress along the way. We ultimately need our foot and ankle to be able to load and produce force under control at a minimum to run, but also handle uphill/downhill loads, and trails with varying and unpredictable terrain. In order to return to running with confidence, it’s important to be able to control single leg dynamic movements in standing as well as plyometric in nature (hopping based movements). There can be creativity involved building on motor control exercises to return to running, but they should still be in some way specific and progressive to prepare for trail running. There are a multitude of options for progressions of motor control based exercises, but here are a few (of many) exercises I’ll issue when appropriate during the rehab process.

Return to Run Confidence Once you can tolerate single leg loading under control with confidence in a controlled setting, we can return to running with a focus on gradually progressing the challenges of terrain, speed, and duration of running. Below you will see a general continuum of factors to be progressed as confidence improves at the foot/ankle.

I would typically recommend progressing one challenging variable at a time, rather than multiple at once, to really ensure that you’re gaining confidence and feel ready to progress. As the last thing you’d want to occur is another LAS which sets you back again. Closing Thoughts As a trail runner, there’s a high potential you may deal with a varying degree of LAS from minor to severe (but hopefully not!). My hope is that you now have some ideas and strategies to consider implementing when managing your own LAS. Ensure to focus on restoring ROM, walking gait mechanics, strength, movement/motor control, and confidence so you can return to running! Sean RimmerPhysical Therapist & Running Coach at Run Potential Rehab & Performance in Colorado Springs, CO.  North Cheyenne Canyon, Colorado Springs North Cheyenne Canyon, Colorado Springs With the summer season now in the rear-view mirror and with winter lurking closer by the day, for most of us in North America the trail race season is coming to a close. That means the trail running off-season is upon us. Depending on where you live, the off-season is highlighted by colder weather, shorter days, and limited trail races available. For some of us, that may mean a “hard stop” with running for several weeks or months, some of us may spend more time cross-training/strength training and less time running, and some others may continue to build their training as if there’s no true off-season. The question is, what should you do? In this article, I will explain some considerations for how to spend the off-season including variations of training. But, consider everything with a grain of salt, as the off-season is highly dependent on each individual. Off-Season Timeline Considerations At this time of the year I often find myself planning out my races for the upcoming spring, summer, and fall. Typically, my off-season timeline will vary based on when my races are planned for the following year & my current state of health. Ideally, if I have a goal race in March, my off-season may be several weeks to months shorter than if my first goal race is in June. However, if I feel a bit “run down” either physically or mentally, or if I’m still dealing with some sort of running-related injury from the year, my off-season timeline could look vastly different. So again, it really is dependent on the individual. I’ve never been someone who does well continuing to search for peak fitness at all times of the year, nor do I believe that is a healthy approach. Though a small percentage of individuals can achieve that (arguably a very small percentage), most of us will often stay healthier if we reduce our running in the off-season and shift focus. This will potentially benefit you in remaining healthy, but also by reducing the risk of mental burnout. I recommend shifting focus in the following ways:

By no means is this an exhaustive list, but more so considerations that have worked well for a multitude of runners to aid in preventing mental burn out and reducing injury risk. I will elaborate on each specific bullet point and the following sections. Reduce Total Running Volume Reducing your weekly running volume can vary by running less frequently (ie. 3 days instead of 5 days), but also by reducing total time/mileage spent running. There’s no perfect answer for a reduction in volume, as some people may drop their total volume by >50%, some 20%, or some may just do 1 day less of running. Finding the sweet spot for you is something you need to test. I often recommend most runners to still remain running 3x a week to maintain some base aerobic fitness and mechanical stimulus to the activity; the other days may be filled with a combination or rest, strength training, or cross training depending on the person and situation. Change The Run Environment If you’ve spent the fall and summer on certain trails, it can be a nice mental stimulus to change it up. Now, if you're 100% all in on trail running only, I get it. So what I recommend is finding new trail areas to explore or run. Here in Colorado Springs we are pretty spoiled with the variety of trails. I often find myself spending a lot of time on certain trails or routes due to enjoyment or convenience, but it’s a nice change when I either find new trails or vary the trails I usually don’t run on during the summer months. This can be a nice novel change for our brains bringing a different sense of enjoyment. Changing the running environment can also provide variability in the mechanical stimulus to your body which can be a healthy alternative to always running on the same terrain. I find myself running more on the roads this time of year, partially due to accessibility, but also due to working on some weaknesses, and for me that’s flatter and faster speed based training. But for some of you this could also mean finding a local track, utilizing a treadmill, or just finding new areas or routes to run. The key to changing the environment is novelty!  Improve Your Run Weaknesses I know for myself that most of my summer and fall season were spent running trails, and specifically with a healthy amount of climbing and descending in the high country. That typically means a combination of running at a relatively slower pace on steeper climbs, intermittent hiking, and enjoying the technical to flowy downhills. What becomes a relative weakness during the summer months is my running speed and efficiency on flatter terrain. Simply, due to the fact that my musculoskeletal system and nervous system are “out of tune” with that type of running. As I’m writing this article, I’ve been focusing more on my running efficiency and speed on the road and track. And though I’m still getting out on trails 1-2x a week, I’m enjoying the shift of focus to working on my current weakness. Depending on your running goals for the next year, this can be a nice time to improve on your running efficiency and turn over which can feed into the trail running season come spring and summer. What I will say from experience, and from the experience of other strong trail runners, is that speed and efficiency on the flatter terrain does translate into your climbing efficiency. So keep that in the back of your mind during this time of the year!  Cross-Training When it comes to cross-training, there appears to be a love-hate relationship in most runners I know. Some runners really enjoy the balance of cross-training in their training program especially during the off-season, and other runners just purely want to run. I find that the individuals that “love” cross-training really enjoy the activity (ie. cycling, skiing, etc) itself rather than necessarily doing it just to supplement their run training. I myself really enjoy Nordic skiing in the off-season as well as gravel cycling (weather permitting of course!). So for those of you who love cross-training there’s no need for me to sell it! But, for those of you who despise cross-training, here’s why it can be beneficial:

There’s also something to say about cross-training outside as this can provide some change in scenery in comparison to a machine in the gym. But ultimately, if you can find a cross-training activity you enjoy, that’s the one to stick with!  Strength Training I’m a strong advocate for strength training all year round to improve load tolerance in our tissues, but also by addressing areas that get neglected in running. During peak run training, I may strength train 1-2x a week to 1x every other week, but during the off-season, I often add in strength training 2-3x a week consistently. I’ve found that an uptick in strength training during the off-season helps my climbing and descending as I return to more frequent trail running. In the off-season I tend to focus on increasing my strength capacity with bigger movements like the dead-lift, squat, split-squat while also focusing on plyometrics to improve my energy storage and release for running. Though I find value in strength training to specifically improve in areas needed for running, I also believe it’s important to strength train tissues through a full range of motion for general tissue health and resiliency. The off-season can be a time to further explore the gym and/or movements that have been dormant during peak run training! Rest & Recovery Time Lastly, the off-season is a time to enjoy more true “off days”. Take advantage of social gatherings with friends or family, getting proper sleep, or enjoying other activities you may have sacrificed during peak training. When we heavily prioritize our runs during peak training, we tend to miss out on the other pieces that bring value to our lives. I also think there’s something to be said about the natural cycle of sunlight. As we head into the winter season, there’s dramatically less daylight compared to the summertime. Throughout human history the winter season has been a time to rest and recover after a spring, summer, and fall season of doing work. Unfortunately, in today’s modern society we’ve become a bit “out of tune” with the natural cycle of seasonal changes. What I recommend is listening to what your body is telling you this time of year (not to say you shouldn’t listen to your body at other times of the year), as there’s usually no need to “push” your training. More intermittent rest days will be more beneficial to you than harmful as we approach a new cycle of training in the new year!  Closing Thoughts When it comes to the off-season for trail running, there’s no perfect plan for any specific individual. The past year of racing, training, and potential injuries can dictate your off-season, as well as your future racing schedule plans. My recommendations are to reduce total training volume and to change things up in the off-season. Following these recommendations can aid in reducing physical stress and mental burnout. As for most of us non-professional runners, it’s about longevity in running and enjoying the process for a lifetime! Written by: Sean Rimmer, Physical Therapist & Running Coach at Run Potential Rehab & Performance in Colorado Springs, CO. “ Regain your confidence to run pain free & to your potential”. BRIAN METZLER - Published Sep 25, 2023 Original article by Boulder based, Brian Metzler, for TrailRunnerMag.com  Swiss runner Remi Bonnet en route to winning Pikes Peak Ascent in 2022. PHOTO: PHILIPP REITER / GOLDEN TRAIL SERIES Swiss runner Remi Bonnet en route to winning Pikes Peak Ascent in 2022. PHOTO: PHILIPP REITER / GOLDEN TRAIL SERIES The Golden Trail World Series is elevating the exposure—and clout—of ‘sub-ultra’ trail racing Late on the night of September 16th, several of the world’s best trail runners could be found dancing and frolicking in costumes at the Buffalo Lodge Bicycle Resort in Manitou Springs, Colorado. They’d run 13 miles up to the 14,115-foot finish line of the Pikes Peak Ascent that morning, and now Switzerland’s Rémi Bonnet and American Sophia Laukli—the race winners—were celebrating in style with dozens of other competitors who participated in the latest stop of the Golden Trail World Series international race circuit. The post-race party included plenty of adult beverages, dancing to the tunes of a DJ, the community drinking from a shot-ski and, later—perhaps because of the liquid consumed off that shot-ski—some spontaneous unicycle and tricycle riding from the lodge’s collection of velocipedes. Now in its fifth season, the Golden Trail World Series--a Salomon-sponsored lineup of high-profile and very challenging mountain races around the world—is all about three things: fast and frenzied made-for-TV trail racing, enticing thirst-trap promotional content, and endless amounts of rowdy fun that matches the high-energy running experiences. In many ways, it’s at the opposite end of the spectrum of the more staid cavalcade of fun in the ultrarunning world. That’s not a knock against ultra-distance races, but more a hint of the growing excitement brewing in the mountain running scene. This year’s Golden Trail races range in length from 21K to 42K—roughly half-marathon to marathon distances—which means there is always time to party later at night. “It’s fun because it’s based on short and fast trail racing, which is what I love,” says Allie McLaughlin, a Hoka-sponsored trail runner from Colorado Springs. “It’s just a different vibe than a lot of races.” Overall, there are a lot more shorter-distance mountain running events and participants than there are in the ultra-distance scene, but for years ultrarunners and key races have gotten most of the attention. “I think it’s much more approachable,” says Dani Moreno, an Adidas-Terrex pro from Mammoth Lakes, California. “If you told someone who wanted to get into trail running that they could only do a 100-miler, most would say, ‘Uh, no thank you.’ And I get it because when I first started trail running, I was asked, from the get-go, ‘When are you going to do your first 100?’ That was always the conversation, but it took me five years just to do a 50K. But the point is that the performances of runners at shorter distances are just as impressive as the runners doing longer distances.” Excerpt from "STORIES FROM THE 2023 PIKES PEAK ASCENT & MARATHON" by Peter MaksimowPosted on October 11, 2023 - Trailrunner.com  Cropper (left) and Delaney (right) at the start line of the PPA. Photo: Peter Maksimow. Cropper (left) and Delaney (right) at the start line of the PPA. Photo: Peter Maksimow. One local Manitou Springs resident, who is very new to trail running, having only done his first trail race in November of 2022, excitedly mingled at the start line of the PPA as he took in the nervous energy of those racing. You could feel his excitement, and he exuded the enthusiasm of trail running! One could say Diarra Cropper, who goes by “D” amongst his friends, stands out from the trail running community. Although his newly found excitement for the sport is common with many people who discover trail running, he tends to stand out in large part because of his physical stature at 6’2”. He stands out in larger part because he is black, a rare occurrence in the homogeneously white-dominated sport of trail running. Cropper did not run the PPA or PPM–he is currently training for his first 100-mile race at Javelina 100 in October–but he was involved in the weekend festivities and supported his good friend Derico Delaney, who participated in the PPA. Both Cropper and Delaney sported “Black Men Run” shirts, a nationwide organization with chapters in major cities. Their mission statement reads: To encourage health and wellness among African American men by promoting a culture of running/jogging to stay fit resulting in ‘A Healthy Brotherhood.’ The most visible black mountain and trail running athlete for the last decade and a half has been the 23-time National Champion and 9-time World Champion, Joseph Gray. With his huge athletic success, he has gained a large platform and utilized it to be an outspoken advocate for getting more black athletes into the sport. I had the great opportunity to join Cropper and Delaney on a recent trail run through the Garden of the Gods to learn more about his history and trajectory into trail running. In high school, Cropper was a sprinter and hurdler in track & field, but his main sports were football and basketball. After a serious injury on the basketball court during his sophomore year of college, his collegiate athletic career came to an abrupt end. After college, Cropper became a semi-pro basketball and volleyball player, touring around Colorado and making a meager income. In the summer of 2021, during a pickup basketball game, he came down on his ankle wrong, culminating in a ruptured Achilles tendon. In an effort to get back to what he loved, he committed himself to aggressive physical therapy to get the Achilles back to proper function. That commitment worked, as he came back eight months later to run his first 5K, completing it in 30 minutes. He continued that progression and ran his next 5K in 25 minutes. In his most recent 5K, he made another huge improvement and finished in 19 minutes. In his comeback to health, he found the love of running and completed his first trail half marathon in November of 2022. Fast forward to our run in the Garden of the Gods, where Cropper was sporting a brand new pair of Speedland GS:PGH that he received in the mail the day before. The excitement that comes with any fresh pair of running shoes was very apparent. At the conclusion of the run, Cropper was sold on the shoes and has since accepted a sponsorship deal from Speedland. D has come a long way in a short period of time and still has a long way to go in what appears to be a very bright future! To read more, check out "STORIES FROM THE 2023 PIKES PEAK ASCENT & MARATHON", by Peter Maksimow at Trailrunner.com.

Original post by Golden Trail Series powered by Salomon16TH SEPTEMBER 2023, Start 7:00 AM, 21KM, 2,382M V+ MANITOU SPRINGS, USA  Photo Credit - Salomon Photo Credit - Salomon Despite the snow on the Pikes Peak Ascent race, Rémi Bonnet smashed Matt Carpenter’s 30-year-old record and Sophia Laukli was triumphant in the women’s race. A 30-year-old record! Everyone thought the record was unbeatable, especially due to the weather conditions and a thick layer of snow that had fallen the day before on the upper reaches of the course route. But, Rémi Bonnet (Salomon/Red Bull, Switzerland) had the resources no one was expecting! 1h58’30 on the clock and the Swiss rounded the very last bends of the legendary Pikes Peak climb. A final burst of acceleration and the stopwatch revealed: 2h00’20, 46 seconds faster than Matt Carpenter’s time. "I knew the altitude was the crux," confided Rémi Bonnet at the finish line. "I trained and slept in a hypoxia chamber for 20 days before coming here and today I suffered much less from the effects of altitude. I’m really pleased to have beaten this record! People thought it was impossible, but I did it and I’m really proud to show who the world’s best climber is! Now I need to come back and go under the 2-hour barrier!" Patrick Kipngeno (Run2gether, Kenya) took second place also clocking a fantastic time: 2h04’09. "I’m very happy with my race and this second place. Rémi was on another planet today, it was impossible to keep up with him. I led the pace in the first part of the race but just as I took water, he forged a gap. I’m really pleased because it’s my first time in USA and my first ever race on snow. It is the second time in a row that I’ve finished second on the Golden Trail Series circuit and I’m planning on giving it my all in Mammoth to chase down a victory." Eli Hemming (Salomon, USA) rounds off the podium. "I’m very satisfied with this third spot! Every year I get closer to victory so that’s a good thing. Honestly, Rémi was on another planet today but I’m really pleased with my time." Sophia Laukli, in the lead before the Grand Final With three victories under her belt, Sophia Laukli (Salomon, USA) cannot be caught up with before the final, so the American will arrive in Italy leading the women’s ranking. "At Sierre-Zinal I was thrilled to have been able to run a tactical race, but here I started stressing out when Judith overtook me. In the end though, I managed to stay calm and gave a shot at being tactical again by waiting for the final 4 kilometres to attack, and it worked, so I’m really happy. It’s my first Golden Trail Series victory on home ground in the USA, and I also know I’m out of reach in the overall rankings before the final." This time, Judith Wyder (Hoka/Red Bull, Switzerland) had to be satisfied with second place, after her victory at DoloMyths Run in July. "I’m happy with this result, I couldn’t have done any better. There was a moment when I thought I could win the race as I was leading all the way to the end of the forest but then Sophia overtook me, and I realised she’d just been biding her time behind me until then and she was stronger than me today!" Anna Gibson (Brooks, USA) capped off the podium. "I’m so happy with this third place. I tried to take it easy because this is the longest race I’ve ever done, and with the elevation gain and altitude I wanted to keep some in reserve for the end. I’m amazed I finished third in front of all these athletes, it’s incredible!" The last stage at Mammoth The Golden Trail World Series will now be heading to California for the last stage in the season before the Grand Final in Italy. See you on 22nd September for the Mammoth 26K. Results Men 1 – RÉMI BONNET (SALOMON/RED BULL – CHE): 2:00:20 (+200 pts) 2 – PATRICK KIPNGENO (RUN2GETHER – KEN): 2:04:09 (+188 pts) 3 – ELI HEMMING (SALOMON – USA): 2:07:40 (+176 pts) 4 – SETH DEMOOR (USA): 2:09:47 (+166 pts) 5 – JOSEPH GRAY (HOKA – USA): 2:11:19 (+156 pts) Women 1 – SOPHIA LAUKLI (SALOMON – USA): 2:35:54 (+200 pts) 2 – JUDITH WYDER (HOKA/RED BULL – CHE): 2:39:35 (+188 pts) 3 – ANNA GIBSON (BROOKS – USA): 2:43:59(+176 pts) 4 – MALEN OSA (SALOMON – ESP): 2:47:23 (+166 pts) 5 – SARA ALONSO (ASICS – ESP): 2:48:13 (+156 pts) Dr. Allen LimSkratch Labs Founder & Sports Physiologist  When preparing to do your best in a competitive event or training, it goes without saying that proper food and drink is a critical piece of the puzzle. But, as much of an emphasis as athletes put on what to eat and drink, I often see them making even bigger mistakes with when they consume their food and hydration. Those mistakes can manifest in a host of negative consequences that range the gamut from up-chucking a pre-workout meal to simply not having the energy to maximize a workout. To help prevent this mistiming woe, below are a handful of guidelines gleaned from years of well-timed and not so well-timed experiences that highlight some important tips about how to time your nutrition before, during, and after your next workout or race. Of course, everyone is different and what may work for some, may not work for you. So as always, it’s imperative that you treat yourself as your own experiment and learn what works best for you. After all, timing is everything! Pre-Workout 1) Eat and Drink 3 Hours Before. For longer workouts lasting more than 2 to 3 hours, it’s really important that you eat a substantial meal that makes you full and satiated at least 3 hours before the start of the workout and to drink enough water to quench any sense of thirst. Doing so will ensure that your food is completely digested and absorbed, that you’ve got plenty of time to drop the proverbial “kids” off at the “pool,” that you’re adequately hydrated, and that your blood sugar will be steady. This last point is really important. Eating a meal causes your blood sugar to rise. This, in turn, causes the hormone insulin to be released about 60 to 90 minutes later, which causes that sugar to be moved into muscle and fat cells. If you start exercising 60 to 90 minutes after you eat a large meal, you’ll be starting that exercise right as insulin is peaking. Since a contracting muscle can move sugar into the muscle without insulin, the combination of insulin and exercise can cause blood sugar to dip making you feel like total crud. So give yourself ample time to digest, hydrate, visit the throne, and steady your blood sugar before your big workouts or events. 2) Eat and Drink Right When You Start. Sometimes it’s not possible to eat an ample meal 3 hours before your workout. If that’s the case and you’re worried about not having enough energy for a hard workout, start eating and drinking right when you start the workout. What’s unique about exercise is that unless you’re at a very low exercise intensity, insulin is not normally released when we are exercising since working muscles can uptake sugar without the need for insulin. This means that if you start eating right when you start exercising you won’t experience the crash that is common if you eat too much an hour or so before a workout. You’ll often see athletes right at the start line shoving simple sugars down just before the gun goes off to give them a little boost. Beyond food, another common technique for many athletes is to drink a high to very high sodium solution like Skratch Labs' Wellness Hydration Mix (1500 mg sodium per liter) or Hyper-Hydration Mix (3500 mg sodium per liter) right before very hard and long workouts in moderate to high heat, when getting adequate hydration might be a problem. By drinking a high sodium solution, right before exercising in the heat, the drop in blood pressure and extra space created by expanding blood vessels that are dilating to bring hot blood to the skin to keep you cool, can be offset. But, be careful. Drinking too much at the onset of exercise if it’s cool or when the exercise intensity is low will likely just make you need to pee 20-30 minutes into your workout. 3) Just Get Up and Go. In some cases, if the workout isn’t too hard or long, you can just get up and go, especially in the morning when you’ve just gotten up. The unique thing about sleep is that it’s essentially an overnight fast that re-adjusts the body’s hormonal and metabolic environment, keeping blood sugar steady despite a lack of food. You can take advantage of this in the morning by simply getting up and starting your workout, then having breakfast afterward. This works especially well for lower intensity aerobic workouts where your primary fuel source is fat. So if it’s early, the intensity or duration isn’t that great, and you’ve gotten plenty of sleep, just get up and go. During Workout When in the middle of a workout the amount of food, water, and salt you’ll need will depend on a host of variables including your fitness level, the exercise intensity, the duration, and the environment. Given all the possibilities here, I tend to find that listening to one’s body and bringing ample supplies to allow one to improvise often works better than creating a rigid timetable that may or may not meet a dynamic environment. With that in mind here are some big picture ideas to keep in mind: 1) Hydrate First, Fuel Second. There’s a philosophical problem called Buridan’s Ass, where a donkey, equally as thirsty as it is hungry finds itself exactly equidistant from a barrel of hay and a barrel of water. Given that the donkey wants water just as bad as it wants food and given that it is exactly the same distance away from both, what does the donkey do? Some philosophers believe that the donkey will die because it’s unable to make a decision. Others believe that the donkey’s free-will has nothing to do with the problem and that some external circumstance like a butterfly flapping its wings will move the donkey either towards the water or hay. From a physiological perspective, philosophy doesn’t matter. In most situations, the donkey needs to drink first then fuel. This is especially true during exercise that causes one to sweat a lot. When it’s warm or hot and the intensity is high, the fluid and sodium we lose through our sweat is more likely to negatively impact our performance before depleted fuel stores do. Moreover, a low carbohydrate solution (4 grams of carbohydrate per 100 ml of water) with ample sodium (700-800 mg of sodium per liter) can actually hydrate better than water alone while also providing some fuel. This is because the active transport of sugar and sodium helps to expedite water movement across the small intestine into the body. Thus, when it’s really hot and sweat rates are high, focusing on hydrating with a low carbohydrate solution can provide more than enough energy since the volume of drink needed is also high. With that in mind, there are very few instances, if any, where drinking water alone is better than using a low carbohydrate drink mix with ample sodium. Generally speaking, replacing at least half the calories you burn per hour and keeping your hydration loss under 3-4% of body weight will keep you adequately hydrated and fueled for most workouts lasting anywhere from 2 to 8 hours. 2) Drink When Thirsty. I often hear people say that if you start drinking when you’re thirsty, it’s already too late and that you’ll be too dehydrated to fix it. But, that hasn’t been my experience with elite athletes competing in extreme environments. If anything, if someone drinks beyond their thirst, they run the risk of diluting their blood’s sodium concentration - a phenomena called hyponatremia that can lead to a host of problems and even death in extreme cases. Thirst actually works to try and help control one’s blood sodium level. In fact, one of the important cues for thirst is an increase in blood sodium concentration. As we sweat and lose more water than salt in that sweat, blood sodium concentration increases which makes us thirsty. If we drink plain water, we don’t need to drink as much water as we’ve lost because we lose an appreciable amount of sodium in our sweat (600 to 1500 mg of sodium per liter of sweat). This means that with plain water, we stop being thirsty before we’ve replaced all the water we’ve lost. Said differently, thirst controls sodium balance, not water balance. And this feature of thirst is actually a good thing because even though losing water can be bad for our exercise performance, screwing up our blood’s sodium balance can be bad for life. The easy solution is to replace both the water and sodium that you lose in your sweat. This allows thirst to be a better trigger for maintaining both water and sodium balance. Still, listening to one’s sense of thirst is an important way to time your fluid intake regardless of the type of drink you’re using because keeping one’s sodium balance in check takes priority over water balance. That said, if you weigh yourself before and after exercise to get a sense of your water loss and you are constantly finding that you’re more than 3 to 4% dehydrated and/or you find yourself more dehydrated than your peers and suffering because of it, consider that water volume by itself may not be the problem. If you’re drinking to thirst, you may not be getting enough sodium. Get enough of it and the timing tends to work itself out on it’s own if you listen to your body. 3) Don’t Be Afraid to Eat Real & Solid Food. A lot of the available pre-packaged sports nutrition designed for exercise is deconstructed into some liquid or gel form. I think that the idea is that since athletes need energy quickly when on the go, companies make highly concentrated liquids and gels that are effectively pre-digested so that they empty really quickly from the stomach. But, just because something empties from the stomach really fast, doesn’t mean that it ends up getting absorbed really fast into the body by the small intestine, which sits below the stomach and which is responsible for actually transporting nutrients into the body. On the contrary, most gastrointestinal distress occurs when the rate that digested food empties from the stomach is greater than the rate of intestinal absorption. It’s a classic traffic jam. Put too many cars on a freeway in one spot too fast and you’ve got a cluster. And unfortunately, when there’s a traffic jam in the small intestine the result is a lot of bloating, discomfort, and in some cases an evacuation down the bowels and out the far end of our gastrointestinal solar system - a place that coincidently rhymes with the planet Uranus. The stomach, however, is actually a really decent reservoir for food that slowly churns and digests food then paces that digested food into the small intestine where it can then be absorbed into the body at a consistent and constant pace. But, this function only works if you give the stomach real food or externally pace the entrance of highly concentrated liquid fuels by taking in prescribed amounts on a rigid schedule. While consuming small portions of 10-20 grams of carbohydrate every 15 minutes is certainly a strategy that can work to keep one fueled during exercise, in dynamic race environments, it’s sometimes hard to stick to a very specific interval of food intake. In these situations, don’t be afraid to eat real and solid food and use your stomach as a reservoir that slowly and surely drips calories into your small intestine and body for you. Post-Workout There’s only one piece of critical advice for timing your post-workout refueling and rehydration. And that is to eat and drink as soon as you can post exercise. Here are thoughts to help make that happen: 1) Plan Ahead. This certainly isn’t the easiest or most convenient thing to do, but planning ahead and pre-cooking meals that can easily be reheated to eat immediately after you finish your workout is what I personally prefer. Why? Because, it generally means I’m eating something that tastes better, is more nutritious, and a better value. But, even if planning ahead means you’re going to the sandwich shop down the street, the bottom line is that you want to satiate your hunger and your thirst as soon as you finish your workout. The reason for this is that immediately after exercise, tired muscles are really sensitive to insulin. This means that as insulin is released when you eat, the energy from the food you eat gets preferentially delivered to the muscles that need it the most rather than spreading throughout the body to fat cells or muscles that weren’t active during exercise. The net result is that recovery is improved because one is effectively refueling in a more targeted and faster manner. 2) Use a Recovery Drink if You’re in a Bind. While, there’s nothing like a freshly cooked meal to fast track recovery, if you’re in the middle of nowhere a good recovery drink with about 4 or 5 grams of carbohydrate to 1 gram of protein at about 300-400 Calories with 300-400 mg of sodium per 16 oz serving is a great way to refuel and rehydrate before a more ample meal can be eaten. 3) Time your Workouts to Finish before Breakfast, Lunch or Dinner. There’s something about being an athlete and still functioning in normal society that is sometimes easier said than done. With that in mind and in thinking big picture about proper food timing, sometimes the easiest way to make everything fit is to start with when one trains. Plan your training to finish before breakfast, lunch, or dinner and few will notice that you're living in two worlds (just don’t forget to shower before). It’s important to note that if you’re not an elite endurance athlete looking for a peak performance, the principles discussed also apply to any physical active person who is looking to feel their best when working out. What’s different is the amount or scale. It’s the same music, just at a lower volume. Giving yourself ample time to digest, thinking ahead, and listening to one’s sense of thirst and hunger are same. In fact, for someone just looking to stay healthy and lose a little weight, timing of food around activity is a great way to structure one’s daily meals and meet one’s goals, since using food as fuel or to refuel creates a more natural relationship with the food we eat. Our bodies are designed for physical activity, so use food to be active. For a culture driven by breakfast, lunch, and dinner, a simple tip is to plan your workouts to end before breakfast, lunch, or dinner, so that you’re refueling a depleted tank and revved metabolism. Finally, scale up your calories around your workouts and scale down when you’re not working out. Ultimately, no matter what the intensity or duration of exercise, thinking about how we time food in the context of activity is key to a fitter and healthier life. For a more detailed review of what and when to eat to optimize your active lifestyle, check out Feed Zone Portables for delicious and easy recipes as well as a plethora of food for thought. Sean Rimmer, Physical Therapist & Running Coach at Run Potential Rehab & Performance in Colorado Springs, CO “Regain your confidence to run pain free & to your potential”  photo credit - Peter Maksimow photo credit - Peter Maksimow It’s finally August, and the Pikes Peak Marathon & Ascent weekend is just around the corner. If you’ve been honest with your training, your confidence should be building. At this point, your training environment and focused runs (ie. long runs & workouts) should aim to be as specific as possible for the final month of training; as you only have a few more weeks to peak your training before you begin your taper. So what might that training schedule look like? Well to start, if you’ve followed some of the training build up from Part 1 & 2 of this training blog series, your training may look like the following:

With about 5-weeks left of total training, I recommend the following general guideline. The next 3-weeks will be your final building weeks followed by a 10-14 day taper period. For the 3 weeks of training build, I recommend the following:

Throughout the rest of this article, I will highlight the quality long run, the running workouts, the taper period, and final tips for race day.  photo credit - Jack Hulett photo credit - Jack Hulett Quality Long Runs The long run should now be the staple effort in preparation for race day for a multitude of reasons. Our long run should be relatively specific in duration to race day, it can include steady-state quality efforts, race day specific practice (ie. run/hike combo), as well as race day nutrition and wearable prep. Think of your long runs now being similar to a “dress rehearsal” for race day. I recommend your long runs being up to 3-5 hours for the Ascent, and 4-7 hours for the marathon. The duration will be based on your expected time, but doesn’t have to be exact. The goal is to allow your body to become conditioned to locomoting for that amount of time in a relatively specific manner for race day. I recommend trying to get a minimum of 4-5 thousand feet of vertical gain for your final few long runs for both the ascent and marathon. If you live in the mountains, this shouldn’t be too difficult to manage. But, if you live in a flatter geographical area, my recommendations are as follows: Use a tread-mill at 8-11% grade or find a smaller hill/bridge and do lots and lots of uphill repeats. Now, the other piece to discuss here is the altitude and most specifically above tree-line (~12 thousand feet in CO). If you live in an area with accessibility to high altitude, I highly recommend doing some of your long run efforts above tree-line. For example, for CO locals that could mean doing a longer 14-er (14 thousand ft peak in CO) which includes uphill running/hiking and downhill running/hiking, or driving up to the summit of Pikes Peak then running down to Barr Camp then running/hiking up at a given effort. So where does the “quality” piece come to play in the long run? By utilizing a workout during or throughout your long run. I recommend a steady-state effort this late in the training to be most specific for race day, as the higher intensity workouts will likely not be as specific to your race effort. An example could look like the following: