Injuries and Trail Running - Considerations for Management of Lateral Ankle Sprains In Trail Runners2/14/2024

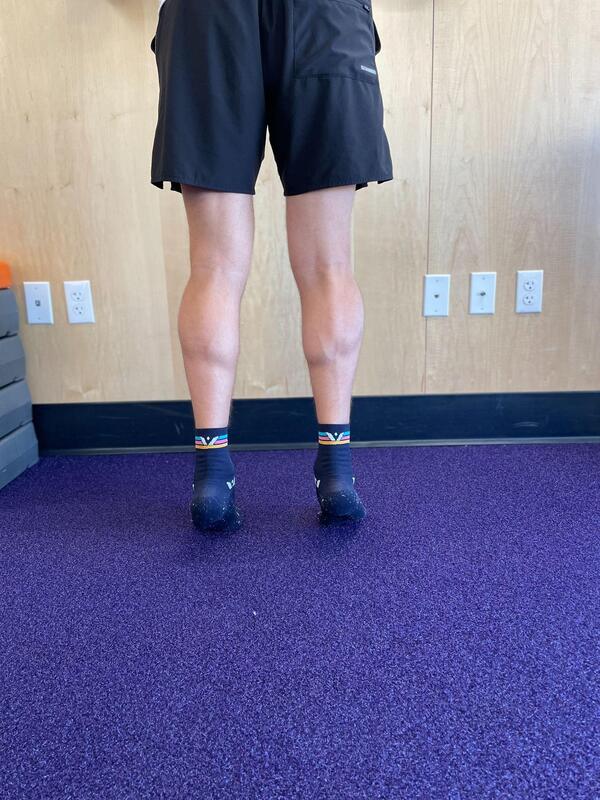

Sean RimmerRunning Specialist Physical Therapist at Run Potential Rehab & Performance in Colorado Springs, CO As trail runners, it’s only a matter of time until a running-related injury (RRI) occurs as that’s the unfortunate reality of our sport. A RRI can occur due to a traumatic event or from repetitive/overuse microtrauma. One of the most common traumatic RRIs I see in trail runners is the lateral ankle sprain (LAS). In this article, I’ll highlight the mechanism of injury and tissues involved within a LAS, considerations for managing the recovery, and returning to running.  Lateral Ankle Sprain (LAS) There’s a high prevalence of LAS in trail runners due to the variable and often less predictable terrain. A LAS often occurs when the foot comes in contact with a rock, root, or unpredictable surface, and the body isn’t able to compensate in time to prevent the foot from rolling outward (excess supination). If the mechanism of “rolling the ankle” is stressful enough on the lateral ligaments between our outer shin bone (fibula) and rear-foot (talus and calcaneus) the ligament(s) is sprained. Ultimately, the ligament sprain occurs when the stress (force) exceeds the ligament’s capacity to prevent excess strain (deformation). The most common ligament that is sprained during a LAS is the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), and second is the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) (The ligaments are named from the bony attachments they share). Ligament sprains are graded based on the severity from grades ranging 1-3: A grade 1 sprain is when the tissue is elongated with micro-tears, a grade 2 sprain is when the tissue involves a partial tear to the ligament, and a grade 3 sprain involves a complete tear/rupture of the ligament. The higher the grade, the longer the recovery time and risk of chronicity. The healing-time frame for grade 1 LAS is typically 2-3 weeks, grade 2 is typically 4-6 weeks, and grade 3 is around 12+ weeks. When I say “healing time” that’s more of a definition of the ligament tissue itself healing, but what’s more important during the recovery process is restoring rear-foot/ankle range of motion (ROM), strength, coordination at the foot/ankle, and confidence to move/return to running. Unfortunately, if you’ve dealt with a LAS at least one time, the likelihood of you dealing with another, or multiple in the future, skyrockets. This is in part due to the ligament itself not being able to return to its previous physiological state of tension, but also if you haven’t restored the foot and ankle ROM, strength, and coordination; this leaves a fault in the movement quality at the foot/ankle which can increase the risk of chronic ankle instability (CAI). Foot & Ankle ROM Considerations In the early phases of a LAS, from days to the first 2 weeks, the primary focus is to reduce local swelling, restore weight-bearing function as tolerated, active ROM as tolerated, and to restore the ability to walk. Once swelling is down and walking is normalized, it's imperative to restore ankle dorsiflexion and rear-foot eversion in weight bearing. The pattern I often see in both acute LAS and in individuals with CAI is that the rear-foot is limited in eversion. When the foot and ankle are limited in dorsiflexion and eversion, this tends to leave your foot in a slightly supinated position (plantar flexed and inverted). This becomes problematic when your foot and ankle can’t properly load into the ground which increases the risk of recurrent LAS. There are a variety of exercises and mobilizations that can improve ankle dorsiflexion and rear-foot eversion, but here are my top 3 that I’ve found to be successful. 1. Active ankle inversion/eversion inverted “U” exercise: This exercise includes slow and controlled foot/ankle movement starting in some ankle dorsiflexion and inversion, moving up into ankle plantar flexion and inversion, then to ankle plantar flexion and eversion, and then ankle dorsiflexion and eversion. Then you reverse. The movement ends up looking like an inverted-U. This can be done with both feet or one, from the ground or on a slant-board, and with external loading all as progressions or regressions to meet the individual.

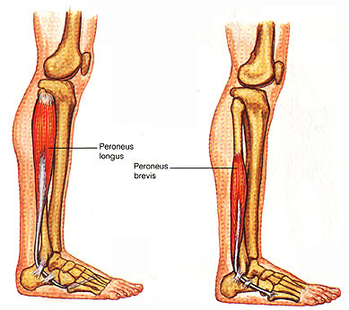

If all of these motions are restored and controlled under active load, we can then build specific strength and movement control to enhance recovery and reduce the risk of CAI. Foot and Ankle Strength Considerations Improving strength around the foot and ankle is also highly important to improve tissue resiliency; though a specific area to improve strength post LAS would be via the peroneal muscles. The peroneal muscles include the peroneus brevis and longus. Both muscles originate in the lateral lower leg and have long tendons that wrap behind our lateral malleoli attaching to our lateral midfoot (peroneus brevis) and the medial plantar surface of our foot (peroneus longus). These muscles help transition the foot from inversion to eversion after initial contact through loading response. The peroneal muscle-tendon units also act as an active “guard rail” to the lateral ankle/foot to control excessive supinatory motion. To improve the functional strength of this muscle group, we need to work the muscle group in plantar flexion and eversion as that’s it’s primary function. My favorite strengthening exercise variation is as follows:

Motor/Movement Control Motor control is dictated by both our past movement experiences and pain. Following a LAS, our motor control is impaired due to pain and the mechanical property changes in the region of the foot and ankle (due to the ligament strain or tear). This is our brain and body’s way of protecting us from not doing more than we can handle on our ankle. Initially, this is a good thing, but as we restore ROM and normalize our walking gait, our motor control at the foot and ankle should progress. Progress in motor control does not occur overnight, but rather gradually with a combination of movement practice/repetition (of how we desire to move) and with progressive movement challenge (ie. more dynamic or progressive load). Furthermore, our motor control progress is on a continuum, from the initial stages of returning to a normalized walking gait to eventually running fast on technical trails. Our body and brain need to take the “stepping stones” through movement practice and progressive challenge to have the movement confidence to progress through the motor control continuum. This means that the rehab process should reflect the progression of loading/challenge of movement to ultimately meet the demands of the end goal (ie. running technical trails). It’s important to note that confidence to move/run should also progress along the way. We ultimately need our foot and ankle to be able to load and produce force under control at a minimum to run, but also handle uphill/downhill loads, and trails with varying and unpredictable terrain. In order to return to running with confidence, it’s important to be able to control single leg dynamic movements in standing as well as plyometric in nature (hopping based movements). There can be creativity involved building on motor control exercises to return to running, but they should still be in some way specific and progressive to prepare for trail running. There are a multitude of options for progressions of motor control based exercises, but here are a few (of many) exercises I’ll issue when appropriate during the rehab process.

Return to Run Confidence Once you can tolerate single leg loading under control with confidence in a controlled setting, we can return to running with a focus on gradually progressing the challenges of terrain, speed, and duration of running. Below you will see a general continuum of factors to be progressed as confidence improves at the foot/ankle.

I would typically recommend progressing one challenging variable at a time, rather than multiple at once, to really ensure that you’re gaining confidence and feel ready to progress. As the last thing you’d want to occur is another LAS which sets you back again. Closing Thoughts As a trail runner, there’s a high potential you may deal with a varying degree of LAS from minor to severe (but hopefully not!). My hope is that you now have some ideas and strategies to consider implementing when managing your own LAS. Ensure to focus on restoring ROM, walking gait mechanics, strength, movement/motor control, and confidence so you can return to running! Comments are closed.

|

©

Pikes Peak Marathon